Based on a Washington Post story by Terrence McCoy — Photos by Bonnie Jo Mount.

Between 1996 and 2015, the number of working-age adults receiving federal disability payments increased dramatically across the country. Rural America experienced the most rapid increase in disability rates, with as many as one-third of working-age adults living on monthly disability checks. This increase has been partly driven by demographic changes that are now slowing as baby-boomers with disabilities age into retirement.

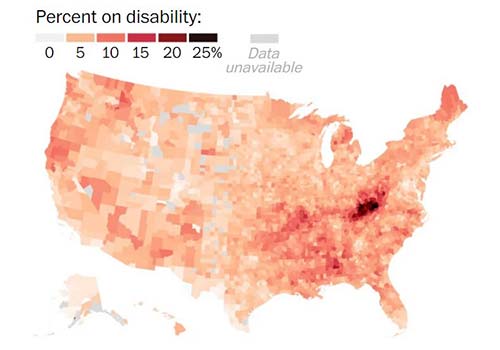

Disability rates by county in 2004

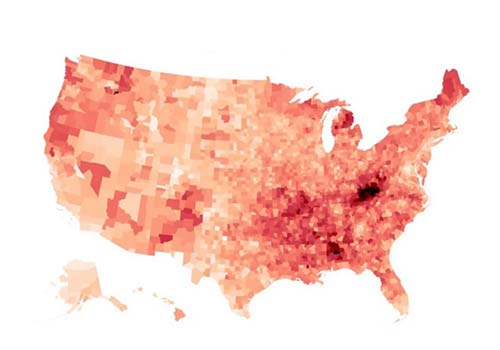

Disability rates by county in 2015

Disability rate includes individuals on SSI, SSDI, or both. Data suppressed in some counties due to small population.

Sources: Social Security Administration SSDI Annual Report, 2004 and 2015; Social Security Administration SSI Annual Report, 2004 and 2015.

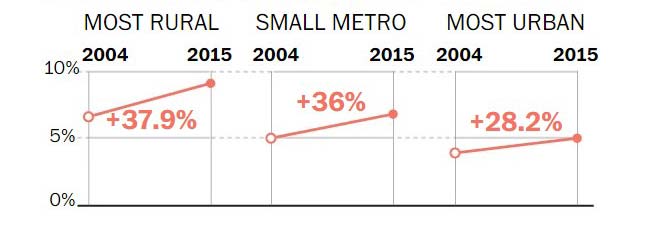

Increase in Disability Unemployment in Rural America

The increases have been worse in working-class areas, worse still in communities where residents are older, and worst of all in places with shrinking populations and few immigrants.

All but three of the 136 counties with the highest rates of disability were rural.

These counties spread out from northern Michigan, the boot heel of Missouri and Appalachia, and into the Deep South. They are largely racially homogeneous. Eighteen of the counties were majority black, but the remaining counties were, on average, 87 percent white.

Most people aren’t employed when they apply for disability — this is one reason applicant rates skyrocketed during the recession.

Full-time employment would, in fact, disqualify most applicants. And once on it, few if ever get off, their ranks uncounted in the national unemployment rate, which doesn’t include people on disability.

While disability rates for working-age people have increased nationwide since 2004, rural counties have seen the steepest increases overall.

Change in disability rate for each group of counties in people age 18-64

Disability rate includes individuals on SSDI, SSI, or both.

Sources: Social Security Administration SSDI Annual Report, 2004 and 2015; Social Security Administration SSI Annual Report, 2004 and 2015 The Washington Post.

Decision to Apply for Disability Benefits

The decision to apply, in many cases, is a decision to effectively abandon working altogether. For the severely disabled, this choice is, in essence, made for them. But for others, it’s murkier. Aches accumulate. Years pile up. Job prospects diminish.

“What drives people to [apply for] disability is, in many cases, the repeated loss of work and inability to find new employment,” said David Autor, an economist with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has studied rising disability rates. “Many people who are applying would say, ‘Look, I would like to work, but no one would employ me.’ ”

In the Washington Post’s examination of this issue, they interviewed Desmond Spencer, a 39-year-old resident of Lamar County, Alabama. At 39 years old and a lifetime of manual labor, he is contemplating applying for disability benefits. Unemployed and in nearly constant pain from an untreated work injury received years ago, he struggles with his desire to work and earn an income, and the reality of his physical condition and lack of jobs in his community. “There’s a stigma about it,” he said. “Disabled. Disability. Drawing a check. But if you’re putting food on the table, does it matter?”

Read the full article:

Disabled, or just desperate? Rural Americans turn to disability as jobs dry up